So your child has impetigo, what now? Advice on what to do, how to soothe symptoms and when your child can return to school or nursery

Impetigo usually clears up on its own after a few weeks, but because of the contagious nature of the infection, it is recommended you visit your GP. Here’s what else doctors want you to know if your child has impetigo…

Debra Waters

Parenting advice, hot topics, best buys and family finance tips delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Impetigo is a skin infection that's very common in young children and very contagious. Thankfully it’s not usually serious and often gets better in 7 to 10 days if you speak to your GP and get the proper course of treatment.

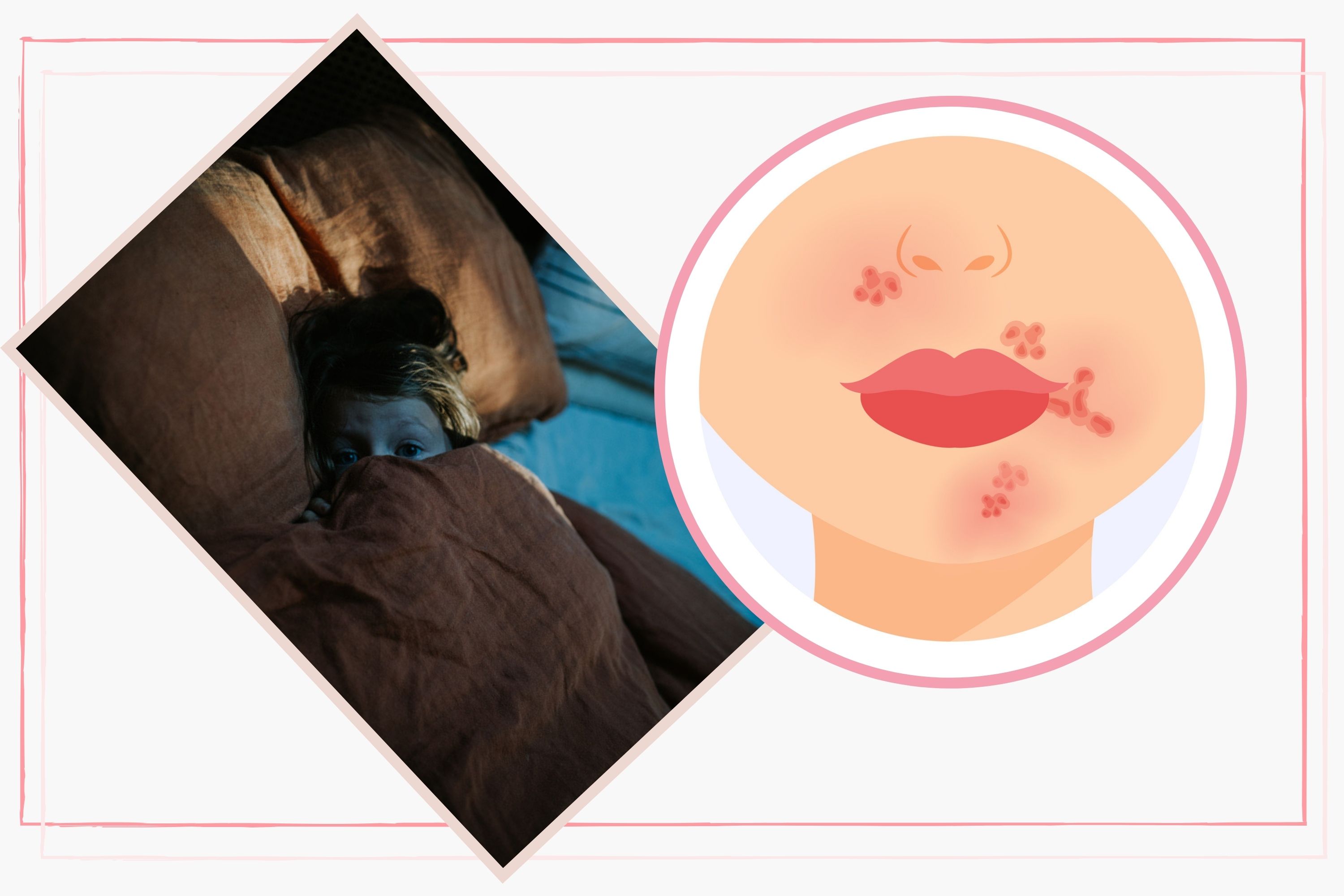

Impetigo is a bacterial infection that causes red sores or blisters on the skin that can be itchy and irritating. It can affect any part of the body but is most commonly found on the face – especially around the nose and mouth. When the blisters burst they leave behind crusty golden-brown patches.

There are three types of impetigo: non-bullous, bullous and ecthyma.

Dr Adam Friedmann, consultant dermatologist at Stratum Clinics, and Dr Ahmed Massoud, Consultant Paediatrician at The Portland Hospital (part of HCA Healthcare UK), both shared their insights and advice on impetigo for this article, so you know what to do if your child catches this common infection and what steps to take to help them recover quickly and fully.

The information in this article is for general purposes only and does not take the place of medical advice. It is essential to be guided by your GP and take note of official NHS advice. You should immediately seek medical attention if symptoms worsen or you are concerned about your child. If you are unsure, concerned about their symptoms, or a rash that has appeared, then it is crucial to seek personalised advice from a doctor as soon as possible.

What causes impetigo?

Impetigo is a skin infection caused by bacteria. The bacterium most commonly responsible is called Staphylococcus aureus. Aureus is Latin for gold, and the bacterium is so-named because it looks golden when grown in a lab.

Dr Adam Friedmann explains, "Impetigo is typically caused by the bacteria Staphylococcus aureus, but sometimes, less frequently, by Streptococcus pyogenes. Non-bullous and bullous are the two most common types."

Parenting advice, hot topics, best buys and family finance tips delivered straight to your inbox.

Impetigo is a very contagious infection that spreads through touch. It usually starts on skin that is already damaged; for example, a graze or a patch of eczema. You can prevent this by making sure cuts and grazes are clean and covered, and by getting treatment for eczema.

The bacteria that cause impetigo can also penetrate the skin via cold sores, chapped skin and insect bites.

Dr Friedmann adds, "The incubation period for impetigo is up to ten days from being first exposed to the bacteria so you won’t see symptoms straight away. The length of incubation will depend on what strain it is (streptococcal infections is approx. 1-3 days and staphylococcal infections is more like 4-10 days).

"The first signs of impetigo tend to be itchy blisters that develop pus and red sores that quickly burst and ooze for a few days before forming a yellow/brown crust. On the whole you'll notice these around the nose and mouth first before they quickly spread to other parts of the body."

What should you do if your child contracts impetigo?

If you think your child has impetigo, the first thing you should do is make an appointment with your GP. As impetigo is so infectious your GP may suggest a phone consultation instead of asking you to bring your child into the surgery.

As impetigo is a bacterial infection it usually requires antibiotic treatment, either in the form of a cream or medicine, which will be prescribed by your GP or health professional.

Dr Friedmann explains, "if only a small patch of skin is affected, an antibiotic ointment used for five days will usually suffice. Topical mupirocin or fusidic acid is very successful in treating mild forms of the condition. However, if the infection has spread to other areas of the body, the doctor may prescribe an antibiotic pill such as penicillin to be taken for seven - 10 days. Erythromycin can be used in those allergic to penicillin.

"After antibiotic treatment begins, healing should start within a few days. Like all antibiotics it’s important to continue to use the treatment as prescribed and not stop early, even if the impetigo has cleared up."

To avoid impetigo spreading to other family members don’t share bedlinen, clothes or towels with an infected person and wash these items at a high temperature after use. You and your child should wash your hands regularly to prevent further spreading. Try to prevent your child from itching the sores or blisters then touching another part of their body, as it also spreads this way.

Occasionally, impetigo can lead to complications such as cellulitis – a more serious skin infection. Monitor your child closely and if the impetigo is not getting better after seven days of treatment, or the symptoms change or get worse, you should see your GP again. You should also speak to your GP if your child has had impetigo before and it keeps coming back.

How do you soothe a child with impetigo?

Impetigo is usually more itchy and irritating than painful. To help make your child feel more comfortable, dress them in loose, light clothing, keep the sores clean and dry (an antiseptic soap will do), and cut their fingernails short or, if you can, put them in mittens or gloves at night to prevent scratching.

Dr Friedmann advises, "Whilst impetigo can feel sore and itchy, sufferers don’t tend to feel too poorly with it. While the infection is healing, gently wash the skin daily with clean gauze and antiseptic soap and to prevent spreading, cover infected areas with gauze bandages or loose clothing.

"To speed the healing process avoid touching patches of impetigo and ensure you wash your hands immediately before and after applying the antibiotic cream/ointment."

Dr Ahmed Massoud recommends, "to soothe a child with impetigo, you can use over-the-counter pain relief medications, and keep the skin clean by gently washing the affected areas with mild soap and water." Always check with your pharmacist or doctor to find out what pain relief medications might be suitable for your child before purchasing.

Can a child with impetigo go to school or nursery?

As impetigo is so contagious you will need to keep your child off school or nursery until the sores are dry and have scabbed over, or until they’ve been on antibiotic treatment for a minimum of 48 hours.

Dr Friedmann states, "During the contagious period it’s advisable to stay away from school as impetigo can spread very quickly through school classes."

How long is impetigo contagious and when can a child with impetigo return to school or nursery?

The NHS website recommends that 48 hours after starting antibiotic treatment impetigo will stop being contagious, or when the blisters have crusted over and dried out – whichever is sooner. Even if your child is showing signs of improvement they should complete the course of antibiotics.

Dr Friedmann explains, "The infection usually gets better in seven to ten days of treatment. As a rule, individuals are no longer contagious once the sores have disappeared. However, this timeframe can be reduced with appropriate topical antibiotics and with effective oral antibiotics the sufferer is usually considered non contagious after about 48 hours of treatment."

He adds, "It’s advisable to keep them off school until the weeping and golden crusting is gone. With treatment this normally takes a few days."

Can adults get impetigo?

Children under the age of five are most prone to catching impetigo, although older kids and adults can be infected by it too. This is especially true if they have a skin or immunodeficiency disorder, diabetes, or are having chemotherapy.

Dr Friedmann says, "In the UK it is the most common bacterial skin infection seen in children, but it can affect people of any age."

"Anyone can develop impetigo, but it's very common in young children (aged two - six years). The bacteria that cause impetigo can infect normal skin, but typically it’s skin that is already damaged (i.e. due to eczema or cold sores, bites, scabies, cuts or grazes etc.)."

"Also, people with a low immunity, undergoing chemotherapy or suffering with diabetes are more prone to developing it."

Does impetigo require contact precautions with other family members?

Yes, impetigo does require contact precautions with other family members, especially people with diabetes or a weakened immune system and babies.

Impetigo can be a threat to babies, in particular to newborns who don’t have the immunity to fight the infection. Take extra steps to avoid your baby catching it, and if they do, see your GP immediately.

You can help your baby by washing and disinfecting toys, bed linen, clothes and towels to prevent further contamination. Wash yours and your child’s hands regularly, and keep them apart from other children in the household until the sores scab over.

Dr Massoud says, "Make sure to wash hands frequently and avoid sharing personal items like towels and toys. Where possible:

- Encourage the child to not touch or scratch sores, blisters, or crusty patches – this also helps stop scarring. Likewise, do not touch your child’s sores whenever possible.

- Do not share flannels, sheets, towels or clothes.

- Wipe down their toys and wash their clothes and bedding at a high temperature.

- Prevent the sharing of food or cutlery with family members.

Dr Friedmann adds, "Impetigo can spread very quickly through families as it is easily spread from person to person by direct contact with the infected skin.

"To avoid it from spreading make sure you look after your skin by keeping sores, blisters and crusty patches clean and dry and covering them with loose clothing or gauze bandages.

"Make sure you wash your hands frequently and it’s also good to wash your bed sheets and towels/flannels at a high temperature. In cases of children, wash or wipe down toys with detergent and warm water.

"Due to the contagious nature of the infection, impetigo can quickly spread to other parts of the body and so it’s imperative that sufferers don’t touch or scratch their sores, blisters or crusty patches – this will also help avoid scarring."

Do you need to take extra precautions if you are pregnant?

Dr Friedmann reassures that "being pregnant poses no extra risk." Pregnant women can catch impetigo if they’re in close contact with someone who has it but because it’s a superficial skin infection it won’t harm a growing foetus.

Dr Massoud explains, "It is quite rare for an adult to get impetigo. This is partly because it is usually caused by the most common bacteria which are present on the skin, and adults usually have more resistance. However, if you have been in contact with a child, or adult, with impetigo and you are pregnant, visit your GP if you develop any concerning symptoms. It is treatable, so there is minimal risk to the mum and unborn child if it is treated promptly."

FAQs

Can you bathe a child with impetigo?

Yes, you can bathe a child with impetigo. Dr Massoud says, "It's important to keep the skin clean, but make sure to use a separate clean towel for the child to prevent spreading the infection. Afterwards, wash the towel and any flannels used at a high temperature."

"Ensure you don’t share their towels with the rest of the family," says Dr Friedmann.

"Sometimes for the antibiotic cream to be as effective as possible it might be best to regularly soak the affected areas with a wet compress to gently help remove the scabs which will allow the prescribed creams to be absorbed by the skin more easily," adds Dr Friedmann.

Can a child with impetigo go swimming?

Children should not go swimming while they have impetigo. Dr Friedmann explains, "During the contagious period swimming should be avoided and it’s probably best to wait until the crusting has completely settled before a child goes swimming to avoid the infection worsening."

"A child should avoid swimming until the sores have healed to prevent spreading the infection to others. It is highly contagious," says Dr Massoud.

Can you travel with a child who has impetigo?

"You should avoid travelling with a child with impetigo until they are better, or 48 hours after they have started on treatment. If it is absolutely essential to travel, ensure to take necessary precautions to avoid spreading the infection." Dr Massoud says.

If you are concerned, contact your airline before you travel to check that you will be allowed to board the plane and you can also request a letter from your GP stating that the child in question is no longer contagious to carry with you while you travel as an extra precaution.

Can a child get impetigo more than once?

Yes, a child can get impetigo more than once. Speak to your GP if your child has had impetigo before and it keeps coming back.

Dr Friedmann advises, "practising good hygiene can really help prevent recurrent occurrences of impetigo - washing hands often and thoroughly and taking regular baths and showers. If you notice your child has a cut or scrape, or is irritated by a bite perhaps, or suffers with eczema, keep a particular eye on their skin and ensure those areas are kept clean and covered. Also keeping nails short and clean is always preferable."

The information on GoodTo.com does not constitute medical or other health advice or diagnosis and should not be used as such. Although GoodtoKnow consults a range of medical experts to create and fact-check content, this information is for general purposes only and does not take the place of medical advice. Always seek the guidance of a qualified health professional or seek urgent medical attention if needed.

Our experts

Dr Friedmann is a UK-trained Dermatologist who trained at King’s College School of Medicine, London. He has worked at many of London’s teaching hospitals including King’s College, St Georges, Hammersmith, Barts and the London and the Royal Free Hospitals. Dr Friedmann is Chief Medical Officer of The Dermatology Partnership and Clinical Director of the Harley Street Dermatology Clinic.

Dr Ahmed Massoud is a Consultant Paediatrician and Endocrinologist at The Portland Hospital, working both in the NHS and the private sector in London at Northwick Park Hospital. Dr Massoud graduated from University College London, trained in General Paediatrics and completed his sub-speciality training in Paediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes at The Middlesex and Great Ormond Street Hospitals. Dr Massoud also has Postgraduate General Professional Training in General Paediatrics in several London Teaching Hospitals and is a Clinical Research Fellow in Paediatric Endocrinology at the Middlesex Hospital.

An internationally published digital journalist and editor, Rachael has worked for both news and lifestyle websites in the UK and abroad. Rachael's published work covers a broad spectrum of topics and she has written about everything from the future of sustainable travel, to the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on the world we live in, to the psychology of colour.

- Debra WatersFreelance Lifestyle Writer