How to talk to children about war, according to a child psychologist

Parenting advice, hot topics, best buys and family finance tips delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

How to talk to children about war can be hard, our instinct is to ‘protect’ and buffer them from the scary and anxious reality of the world.

Why Russia invaded Ukraine, and the fallout from it, is everywhere. On social media, across TV screens, talked about in aisle 5 at the supermarket. All this exposure makes it even easier for children to pick up on.

Lee Chambers, Child Psychologist tells us; “It’s certainly a challenging time for children at the moment. After years of disruption from the pandemic, there is now added uncertainty of conflict that is being shared wider than ever before. For many young people, this will be their first experience of being surrounded by war reporting, and they will be naturally curious and trying to make sense of it."

Article continues belowHere our Family Editor Stephanie Lowe, gets the lowdown from a child psychologist and parenting expert on why, how and when to broach this daunting topic with children.

How to talk to your child about war

I'm a huge believer in transparency with guidance when it comes to sharing details with children. Kids aren't stupid. And they are so much more intuitive than we sometimes give them credit for. They pick up on tone, expression and every hushed voice you use. If you don't talk openly - to an extent - it may leave them brooding on worst case scenarios with no end in sight.

A useful place to start is by asking whether your child has heard about the conflict, and if so, what they have heard. Keeping it open ended and light in tone helps to kick start the conversation. It also gives you an idea of their knowledge, and what gaps may need filling and which needs require meeting. I.e. a big hug and a reminder that they’re safe.

I spoke with Ane Lemche, a psychologist and child counsellor with Save the Children, and she says that children around the world might not fully understand what is happening in Ukraine and may have questions about the images, stories, and conversations they are exposed to.

Parenting advice, hot topics, best buys and family finance tips delivered straight to your inbox.

And, while it’s not up to the adult to have all the answers, Lee Chambers, Child Psychologist agrees that parents and carers should look to answer their questions. He tells me, “answer with a calm accuracy, remember that they will pick up on our emotive state and potentially mirror that.”

Also bear ages in mind, Lee warns; “For children who are older, and with a mobile phone, they are likely to have access to social media and older peers, and have already heard various viewpoints. So, when they talk to you, be fully present and provide space for them to be listened to and feel heard.”

He adds; “It’s vital that we don't judge or neglect their concerns. That we give them the ability to express their emotions and normalise their feelings out loud.”

So, instead of ‘don’t be silly, it’s all okay. We’re all okay.’ Try ‘It’s a scary time, I know. It’s okay to feel scared and to talk about it. I'm always here for you.'

According to Lee, it’s important to consider age-appropriate language and depth when it comes to talking about war and conflict. “Ensure to not dismiss their curious concerns while at the same time try not to amplify anxieties with too much detail.”

If your child comes to you with a piece of information that you don’t think is accurate, rather than dismissing it, lead with curiosity.

Ask what their source is, and then work together to cross-reference the information with credible news outlets to test accuracy. He also recommends that now is a good time to support their understanding that many aspects are out of our control. And there are many people working to ensure the situation will be resolved.

Ultimately Lee says; “it goes without saying that we should do what we can to limit children's consumption of the news. And we shouldn't force the conversation or assume that we know our child's perspective without understanding their worries first.”

Kirsty Ketley, Parenting Consultant agrees, "I think for younger children, if they don't seem to be affected by what is going on, then there is no need to bring the subject up.

"If they do mention it, you don't need to over-explain things, just keep it simple and appropriate for their age/stage of development. Parents know their children best, so they will know their child's threshold for information."

Talking to children about war is always a fine balance, but it is the perfect time to ensure you listen, be aware of your own emotions and provide a safe space for your child to feel supported while still able to explore their feelings and fears.

When looking for signs of anxiety, Kirsty says; "Younger children's behaviour might change, they might have nightmares or find it hard to sleep. They might also complain that they have a tummy ache and become quite clingy. They will be struggling to make sense of things. Older children may seem withdrawn, moody, or angry about things they wouldn't usually be upset about.

Ane adds; “What is happening in Ukraine can be frightening for both children and adults. Ignoring or avoiding the topic can lead to children feeling lost, alone and more scared, which can affect their health and wellbeing. It is essential to have open and honest conversations with children to help them process what is happening.”

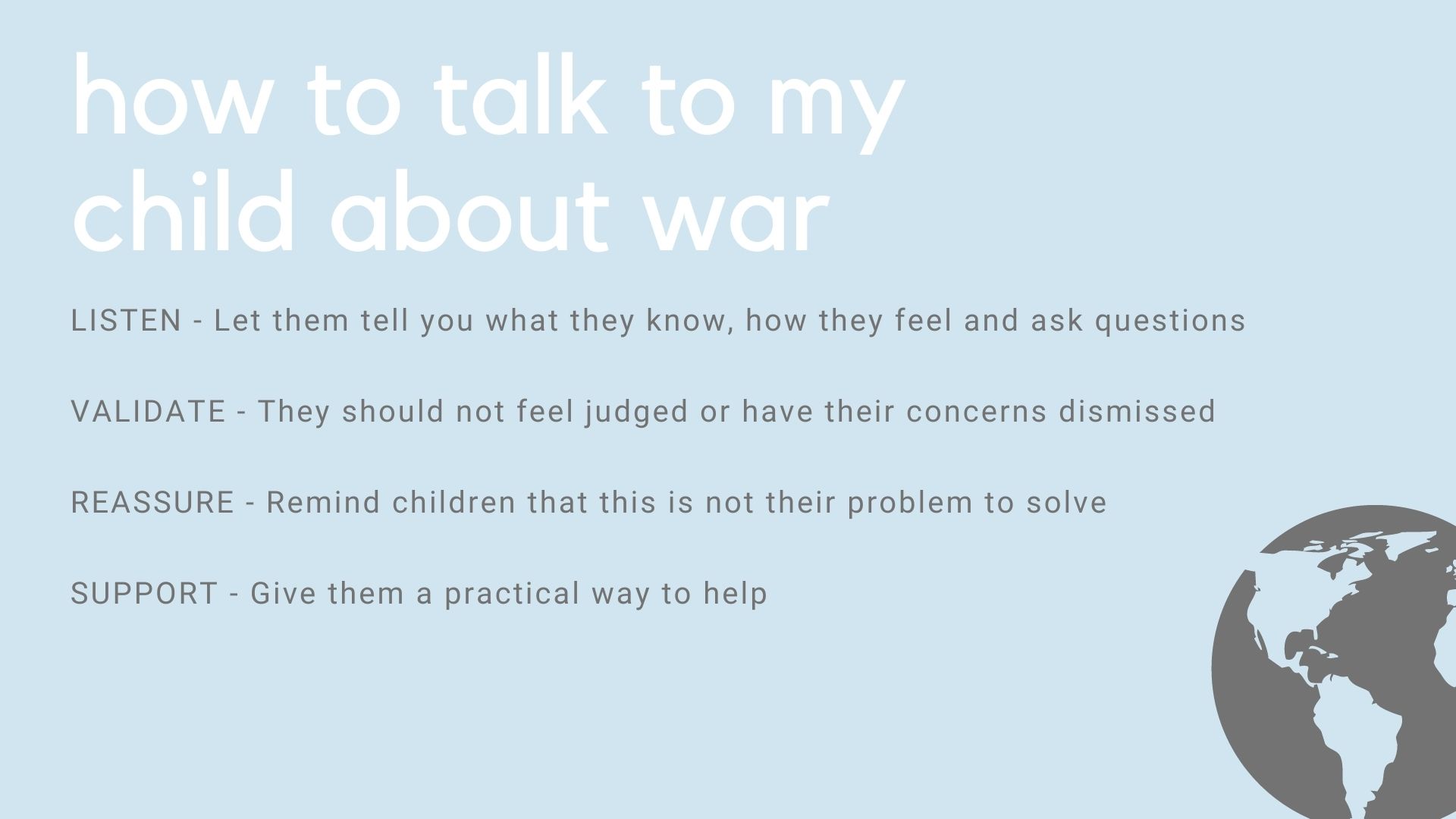

Save the Children recommend Top five Tips;

1. Make time and listen when your child wants to talk Give children the space to tell you what they know, how they feel and to ask you questions. They may have formed a completely different picture of the situation than you have. Take the time to listen to what they think, and what they have seen or heard.

2. Tailor the conversation to the child Be mindful of the child’s age as you approach the conversation with them. Young children may not understand what conflict or war means and require an age-appropriate explanation. Be careful not to over-explain the situation or go into too much detail as this can make children unnecessarily anxious.

Younger children may be satisfied just by understanding that sometimes countries fight. Older children are more likely to understand what war means but may still benefit from talking with you about the situation. In fact, older children will often be more concerned by talk of war because they tend to understand the dangers better than younger children do.

3. Validate their feelings It is important that children feel supported in the conversation. They should not feel judged or have their concerns dismissed. When children have the chance to have an open and honest conversation about things upsetting them, it can create a sense of relief and safety.

4. Reassure them that adults all over the world are working hard to resolve this Remind children that this is not their problem to solve. They should not feel guilty about playing, seeing their friends, and doing the things that make them happy. Stay calm when you approach the conversation. Children often copy the sentiments of their caregivers – if you are uneasy about the situation, chances are your child will be uneasy as well. Kirsty adds: "Younger children who are worried may find looking at the countries on a map to see the distance between them and us, reassuring."

5. Give them a practical way to help Support children who want to help. Children who have the opportunity to help those affected by the conflict can feel like they are part of the solution, such a how to donate to Ukraine. Kirsty agrees and tells: "Kids can feel like they are part of the solution when they fund raise, donate or even by displaying pictures in the window, showing their support. My own kids are taking on a 43 mile walk challenge throughout March to raise money for Save the Children who are working out there, for instance."

Video of the week

Stephanie has been a journalist since 2008, she is a true dynamo in the world of women's lifestyle and family content. From child development and psychology to delicious recipes, interior inspiration, and fun-packed kids' activities, she covers it all with flair. Whether it's the emotional journey of matrescence, the mental juggling act of being the default parent, or breaking the cycle of parenting patterns, Stephanie knows it inside out backed by her studies in child psychology. Stephanie lives in Kent with her husband and son, Ted. Just keeping on top of school emails/fundraisers/non-uniform days/packed lunches is her second full-time job.